Miniatures as “Monuments of a Lost Art” — The Origins and Enduring Appeal of Illuminated Cuttings and Leaves

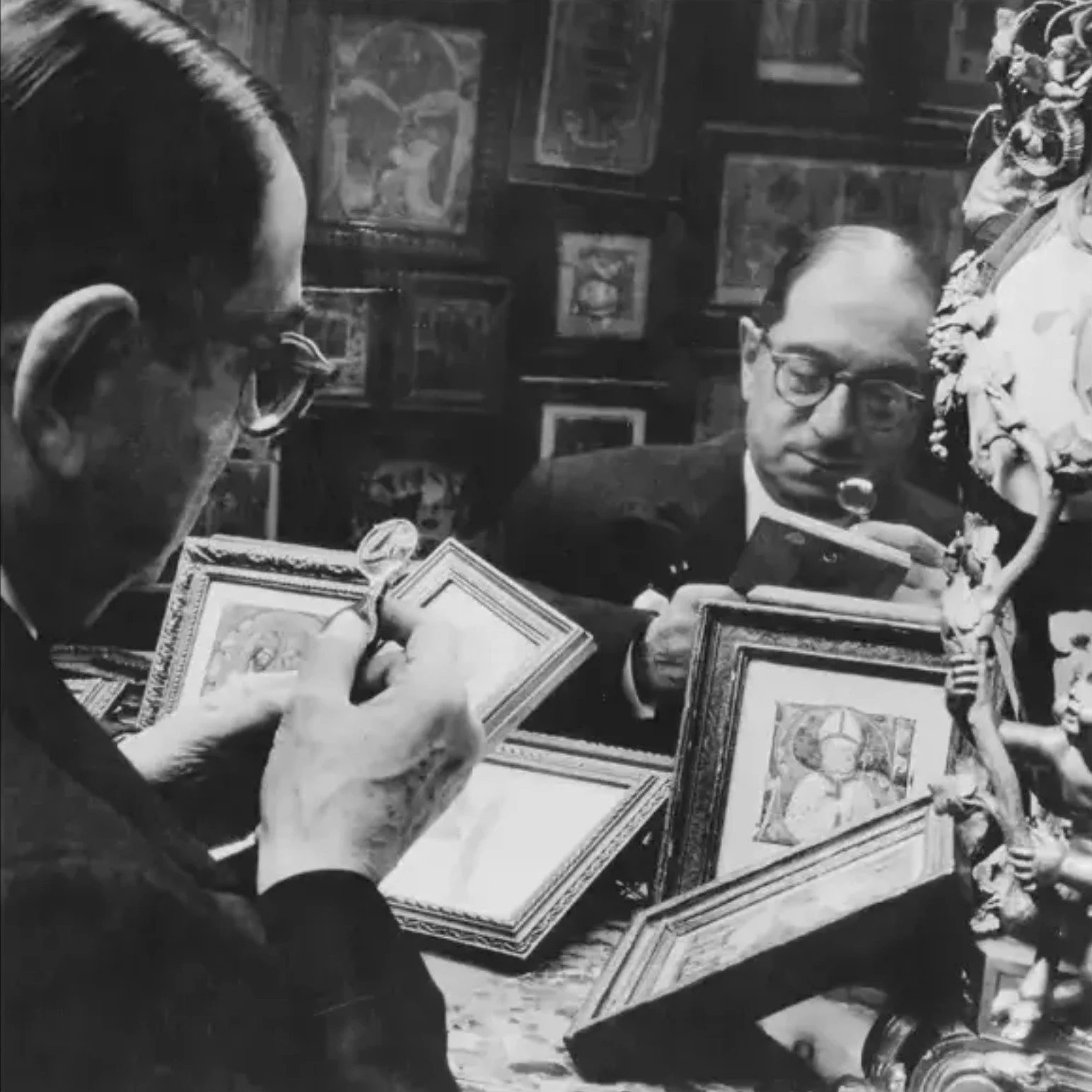

A photograph published in Paris Match in 1963 shows Georges Wildenstein seated in his study, surrounded by framed illuminated manuscript cuttings from his collection

What Are Illuminated Manuscript Miniatures?

Illuminated manuscript miniatures, whether full-page paintings, historiated initials or decorated borders are fragments of a once-integrated art form in which text, image and ornament were conceived as a single visual and intellectual whole. Known variously as illuminations, enluminures, manuscript painting or simply leaves and cuttings, these works were originally created to inhabit books: Bibles, Books of Hours, choir books and other liturgical volumes intended for both devotion and ceremony. In early collecting discourse, such works were often described as, illuminated miniature painting, a term that emphasized scale rather than function and deliberately aligned manuscript illumination with panel and fresco painting within the broader history of art. Though now often encountered as independent works of art, they retain the scale, refinement and painterly ambition of the manuscripts from which they came.

The Origins and Enduring Appeal of Illuminated Cuttings

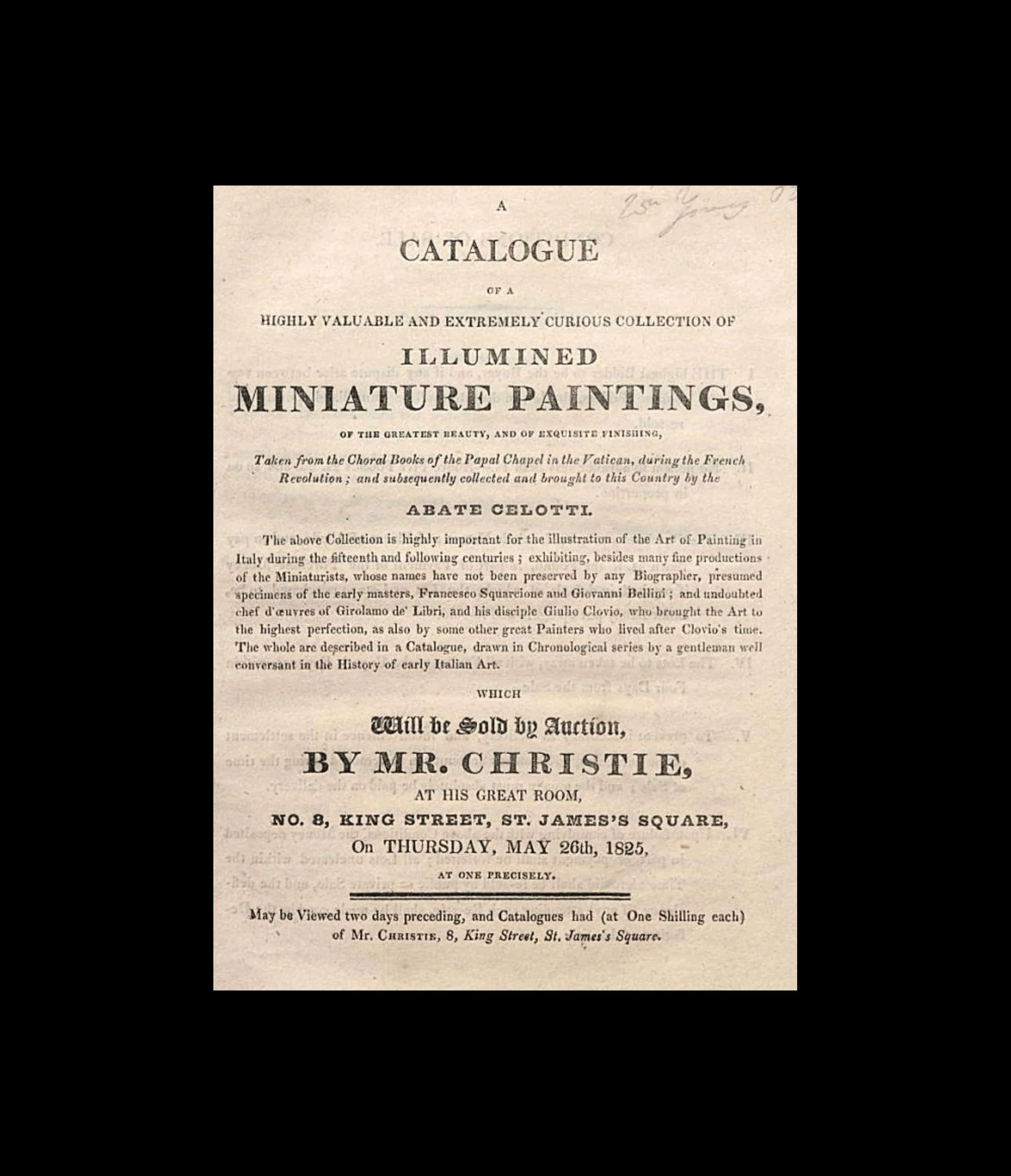

The first public sale devoted entirely to illuminated manuscript miniatures was held at Christie’s in London on May 26th 1825. The sale marks a decisive moment in the history of collecting. Announced under the characteristically expansive title A Catalogue of a Highly Valuable and Extremely Curious Collection of Illumined Miniature Painting of the Greatest Beauty, and Exquisite Finishing…, the auction comprised ninety-seven lots of multiple items taken from the Choral Books of the Papal Chapel of the Vatican. Dispersed during the upheavals of the French Revolution, these monumental manuscripts had been gathered, dismantled and brought to England by the enterprising dealer, bibliophile and former cleric Luigi Celotti. The catalogue itself framed the material not as antiquarian residue, but as a body of works “highly important for the illustration of the art of painting in Italy,” explicitly positioning manuscript illumination within the broader history of Renaissance art.

Portrait of William Young Ottley by William Riviere, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, WA1937.106

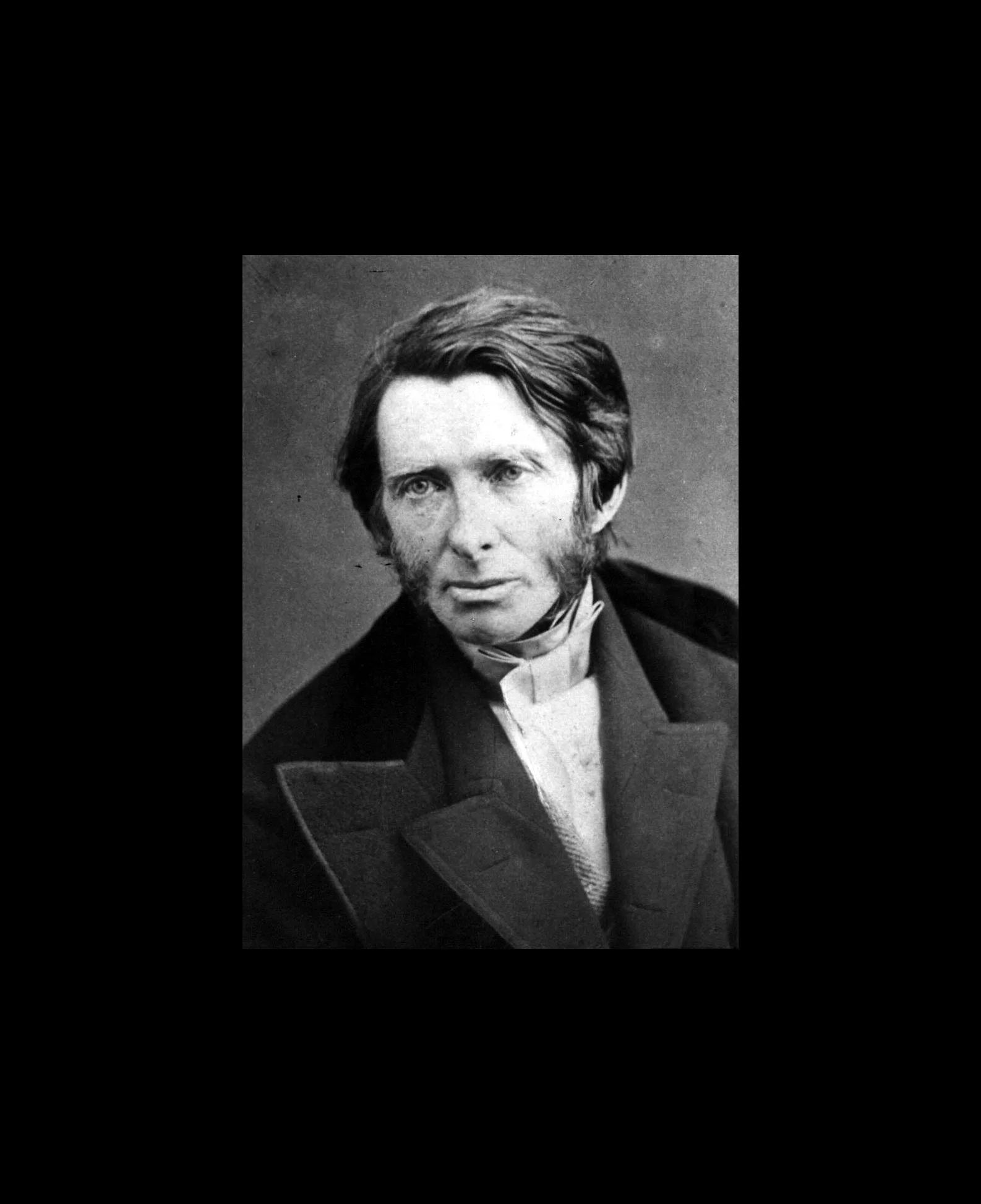

The catalogue introduction was written by William Young Ottley (1771–1836), an early art historian and collector best known for his work on the Italian Renaissance. Ottley drew attention to a paradox that remains striking even today: while many panel paintings and frescoes of the same period have been lost or survive only in compromised condition, illuminations, which are protected for centuries within books often retain extraordinary freshness. For this reason, he famously described them as “monuments of a lost Art,” surviving witnesses to artistic achievements otherwise vanished.

The Celotti sale attracted picture dealers rather than bibliophiles, and they bought heavily and often at high prices. From the outset, illuminated miniatures were valued not primarily as textual artifacts, but as works of art, capable of standing alongside panel painting in both connoisseurship and the market.

Disassembly and the Formation of a Market

Several practical factors encouraged the early trade in manuscript cuttings. In England, customs duties were levied by weight, making it costly to import large, heavy choir books bound in wooden boards. Moreover, many such volumes had fallen out of active liturgical use by the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, having been superseded by printed service books and reshaped by successive waves of religious reform, rendering them functionally obsolete within the contexts for which they had been made. Removing individual miniatures not only reduced shipping costs but transformed unwieldy volumes into portable, marketable works of art.

Photograph of John Ruskin circa 1860’s

Yet economics alone does not explain the phenomenon. The deeper motivation lay in a growing appreciation of illuminations as independent aesthetic objects. This attitude is nowhere more bluntly expressed than in the writings of John Ruskin. Referring to his own practice of dismantling manuscripts, Ruskin noted in his journal with characteristic candor: “Cut up Missal last night—hard work.” Elsewhere, advising a friend on acquisitions, he clarified his priorities: he was interested in manuscripts “interesting in art, for I don’t care about old texts.”

By modern standards, Ruskin’s actions may appear destructive, even barbaric. But they are best understood as a product of Victorian values. Ruskin sought to revive what he saw as a lost artistic tradition, circulating fragments of illuminated manuscripts among craftsmen and students as exemplars of color, design and technique. He drew a sharp distinction between image and text, between art and curiosity, a distinction that has profoundly shaped the history of collecting miniatures ever since.

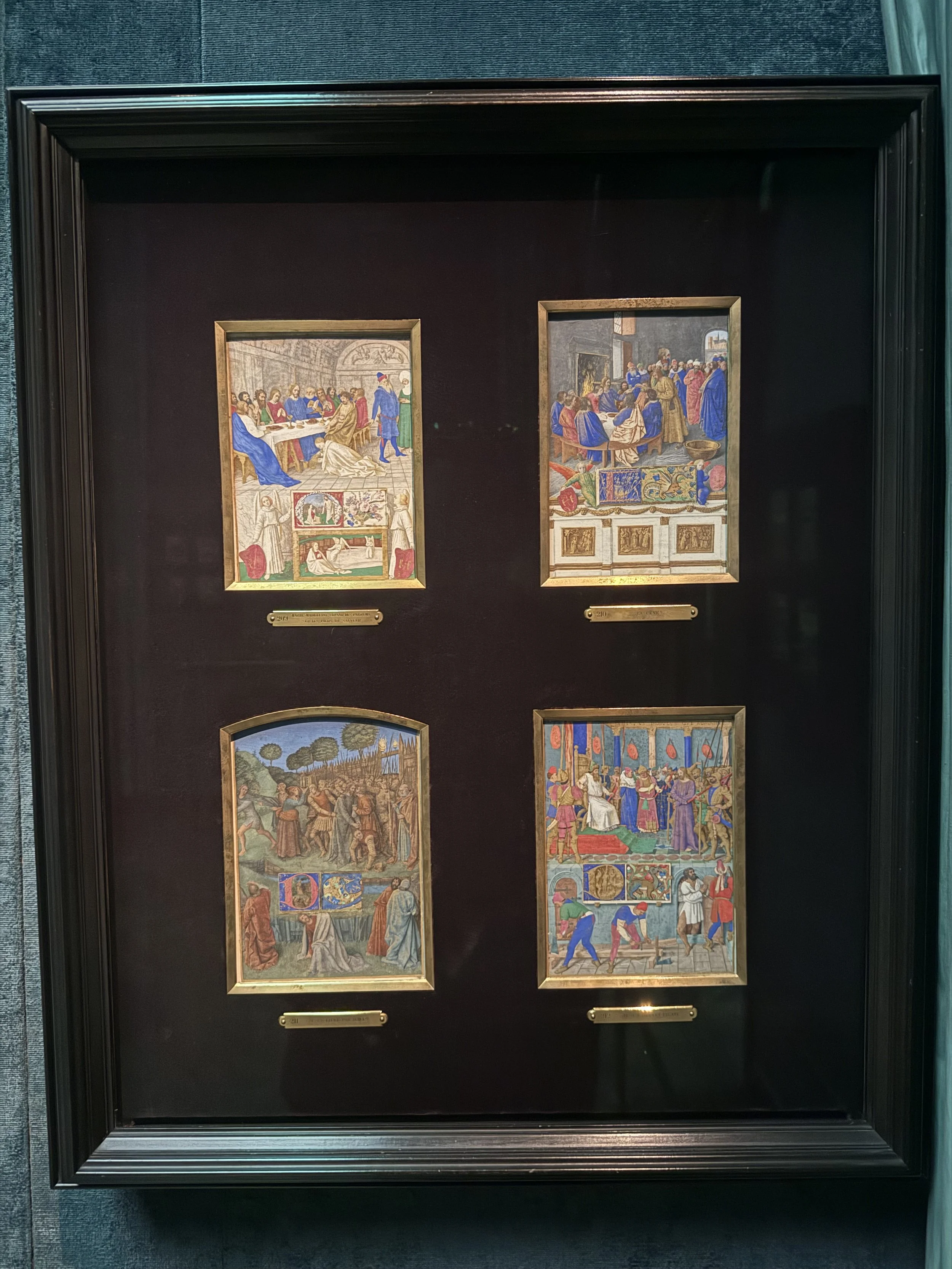

A group of miniatures from the Hours of Étienne Chevalier, illuminated by Jean Fouquet, Musée Condé, Chantilly.

Painters across Media

The artistic legitimacy of manuscript illumination rests in large part on the status of its makers. Many of the greatest illuminators were also painters of the first rank. In Bruges, Simon Bening and Gerard David exemplify a milieu in which the distinction between panel painter and illuminator was increasingly porous. Jean Fouquet and Jean Bourdichon in Tours are among the most celebrated French examples, while in Florence the boundaries between panel painting and manuscript illumination were especially fluid.

At the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli—the famed Scuola degli Angeli—artists such as Fra Angelico, Lorenzo Monaco, Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci, and Battista Sanguini moved seamlessly between easel painting and book decoration. In Florence, unlike much of northern Europe, painters and illuminators belonged to the same guild, responding to commissions across media as opportunity and circumstance demanded.

Complete manuscripts illuminated by such artists are today vanishingly rare and almost always preserved in institutional collections. By contrast, individual leaves and miniatures—often of exceptional quality and historical importance—have survived as independent works, offering a rare point of access to the artistic ambitions of some of the leading painters of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Installation view, Fondation Wildenstein, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

From Private Passion to Public Collections

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, major collections of illuminated manuscript miniatures had begun to form, many of them assembled deliberately from individual cuttings. What originated as private acts of connoisseurship and study would, over time, lay the foundations for some of the most important public collections in the field.

In Europe, the Fondation Wildenstein collection at the Musée Marmottan in Paris comprises over 300 miniatures and remains one of the few permanent public displays devoted to the genre. Other significant collections are held by the Fondazione Giorgio Cini in Venice, the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin, the British Library, and the Musée du Louvre.

In the United States, illuminated miniatures entered major museums and libraries with surprising speed. Today, important holdings can be found at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Morgan Library & Museum, the Free Library of Philadelphia, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the J. Paul Getty Museum, among others.

German Artist, King David in Prayer, historiated initial A from a Gradual, Rhineland, Germany, late 15th century

Why Miniatures Still Matter

Nearly two centuries after Ottley described illuminations as “monuments of a lost Art,” their appeal remains undiminished. Miniatures offer an unusually direct connection to the artistic imagination of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Intimate in scale and luminous in color, they are executed with a level of technical mastery that is often astonishingly well preserved. They also occupy a unique position at the intersection of scholarship, connoisseurship and collecting. Each fragment invites reconstruction: an artist’s hand, of a lost book, an unknown workshop, a forgotten patron or a vanished liturgical context.

Far from being relics of a fragmented past, they remain vital and eloquent witnesses to one of the most refined artistic traditions of the Western world.